Understanding immune tolerance: from Nobel Prize winning discovery to today’s research at SciLifeLab

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine honors discoveries that explain how the immune system avoids attacking the body’s own tissues. At SciLifeLab, researchers are studying the same delicate balance: how immune tolerance is formed, sustained, and sometimes lost.

This year’s Nobel Prize goes to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their discoveries that revealed how the immune system is kept in check. Their work defined peripheral immune tolerance, the mechanisms that prevent immune cells from attacking our own organs and tissues. Read the Nobel Prize press release.

To put this year’s prize in context, we reached out to two SciLifeLab-affiliated researchers whose research is connected to the award-winning science: SciLifeLab Fellow Gustaf Christoffersson (Uppsala University) and SciLifeLab Group Leader Nils Landegren (Uppsala University/Karolinska Institutet).

What the laureates discovered

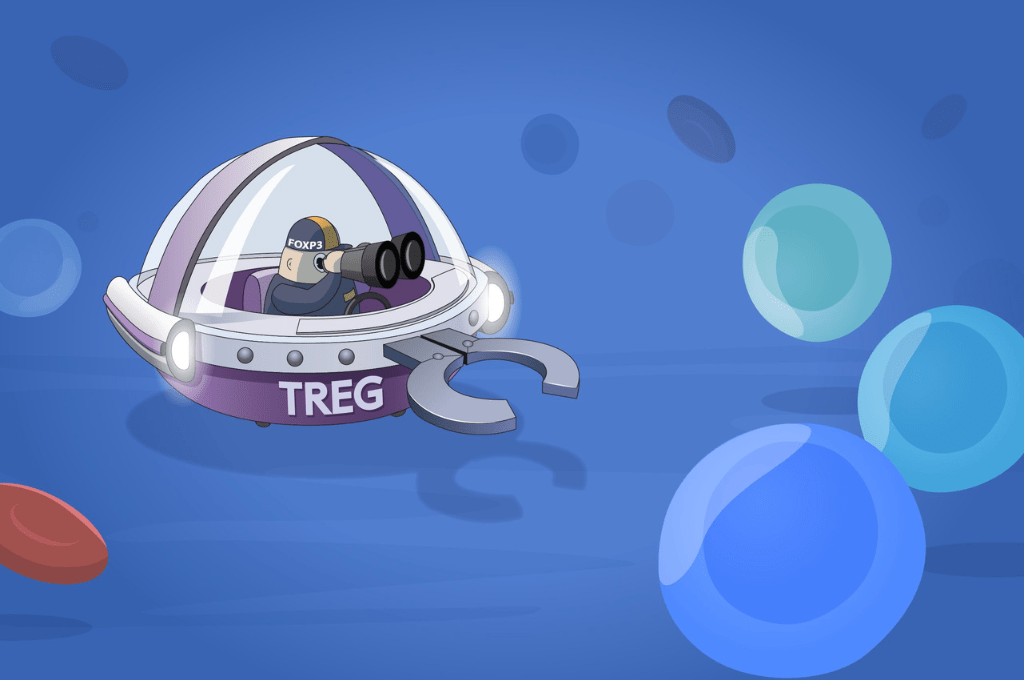

In 1995, Shimon Sakaguchi identified regulatory T cells (Tregs), a cell type that suppresses harmful immune responses. In 2001, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell linked the gene FOXP3 to severe autoimmunity (IPEX) in humans, mirroring a mutation seen in mice. Two years later, Sakaguchi showed that FOXP3 controls the development and function of Tregs. Together, these findings defined a genetic and cellular basis for immune tolerance and opened new paths for treating autoimmunity, cancer, and transplant rejection.

“Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” says Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee.

The SciLifeLab perspective

SciLifeLab Fellow Gustaf Christoffersson studies immune regulation at the tissue level, focusing on type 1 diabetes. Using intravital microscopy, his group follows immune cells inside the pancreas to understand how local mechanisms can restrain autoimmune attack.

“This year’s Nobel Prize laureates have made substantial contributions to our understanding of how the immune system is regulated in both health and disease. Our immune system works in a balance-scale-fashion, with aggressive responses combatting invading pathogens or cancer cells on one arm, and counterregulatory, immune dampening responses on the other. This year’s Prize in Physiology or Medicine for insights in immune tolerance involving the discovery of regulatory T cells, and the protein FOXP3 that controls their formation and function, adds a major and crucial component to the regulatory arm of this balance. Controlling the amounts and activity of regulatory T cells could provide treatments for autoimmunity, where they are needed to dampen the actions of other autoaggressive T cells, and limiting their function in cancer can instead unleash the full potential of the body’s own responses against growing tumors.

Even though the harnessing of these potent regulatory cells has not reached its full potential in treating human disease, large efforts are ongoing to improve these treatments. The expansion of this type of immune cell, and the potential genetic alterations of them, holds promise to provide a truly precision medicine-based therapy where cells can be engineered according to the needs of the patient and nature of the disease.”

SciLifeLab Group Leader Nils Landegren conducts translational research on autoimmune diseases, combining experimental and preclinical studies to explore the fundamental mechanisms of immune regulation and tolerance. His work aims to connect molecular discoveries to clinical understanding, helping to explain how immune balance is maintained, and what happens when it fails.

“This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is very closely connected to our research. We have studied patients who suffer from exactly this kind of immune system defect – a lack of regulatory mechanisms that normally prevent the immune system from attacking the body’s own tissues. These patients develop IPEX syndrome, a hereditary immunodeficiency that leads to severe diarrhea, skin inflammation, and type I diabetes. Their severe condition is a powerful reminder how crucial peripheral tolerance mechanisms are in preventing our immune system from turning against us, giving rise to autoimmune disease.

We have collaborated with researchers in the US, in Sweden, and in France to understand what happens when regulatory T-cells are missing and what their immune system reacts against. We see strong immune responses to proteins expressed in the gut, but also against insulin-producing cells, and other affected tissues, which shows how crucial this mechanism is. We were very pleased to see that this year’s Nobel Prize recognized this fundamental question about the immune system: how it protects us from invading bacteria and viruses while at the same time avoiding attacks on our own body. It is a delicate balance, and when it fails, the consequences can be devastating.”

Through SciLifeLab’s national platforms, Swedish researchers are well positioned to build on this year’s Nobel-winning discoveries.

Media contacts

SciLifeLab Fellow Gustaf Christoffersson

Associate Professor at Uppsala University

018-471 43 25

gustaf.christoffersson@mcb.uu.se

SciLifeLab Group Leader Nils Landegren

Associate Professor at Uppsala University and Affiliated to research at Karolinska Institutet

070-830 83 47

nils.landegren@imbim.uu.se

Illustration: © The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Ill. Mattias Karlén