New method can identify and reveal both B and T cell receptors in human tissue

A new method developed at SciLifeLab, Karolinska Institutet (KI), and the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) can identify unique immune cell receptors and their location in tissue, as reported in the journal Science. The researchers predict that the method will improve the ability to identify which immune cells contribute to disease processes and open up opportunities to develop novel therapies for numerous diseases.

Immune cells such as T and B cells are central to the body’s defense against both infections and tumors. Both types of immune cells express unique receptors that specifically recognize different parts of unwanted and foreign elements, such as bacteria, viruses, and tumors. Each immune cell and its progeny has its own specific receptors, and in each human body there are billions of different immune cells with unique receptors.

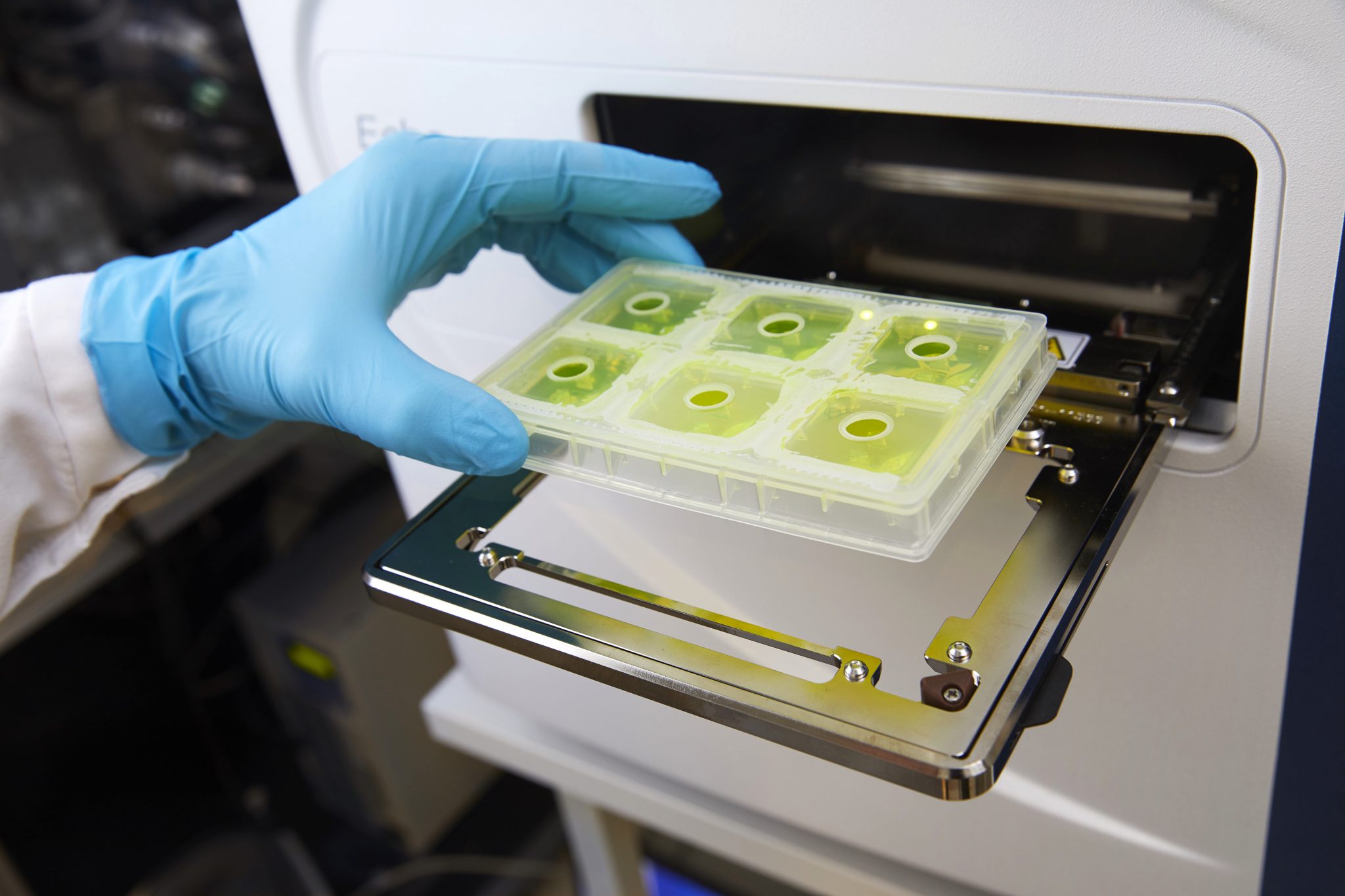

Researchers at SciLifeLab, KI, and KTH have now developed a method that can both identify the different B and T cell receptors and reveal their location in human tissue. Camilla Engblom, one of the study’s three lead authors, along with Kim Thrane (KTH/SciLifeLab) and Qirong Lin (KI), is a recent addition to the SciLifeLab Fellows program. The study was done in collaboration with Frisén (KI) and Lundeberg (KTH/SciLifeLab) lab at SciLifeLab.

“Since activated immune cells are often found close to the targets that they attack, we want to be able to map the cells that are indeed closest to a tumor or infection. It hasn’t been possible to identify both B and T cell receptors in their microenvironments using previous methods,” says Camilla Engblom, SciLifeLab Fellow and assistant professor at KI.

According to Dr Engblom, there is a wide range of areas in which the new technique can be put to clinical use in the future.

“In cancer, the method can identify T cells that potentially attack the tumor,” she says. “They could then be used as cell therapy against cancer. We can also identify unique receptors on the B cells that are released as antibodies in specific areas of the tumor. These antibodies can be produced in the lab with relative ease and eventually give rise to novel therapies. Another field is autoimmune diseases, where the immune system attacks healthy tissue. The new technique could be used to identify the immune cells that do this and increase the chances of finding exactly what it is they attack.”

Jeff Mold, one of the study’s principal investigators and researcher at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at KI, sees the new method as an important step forward.

“Identifying these unique immune receptors is like trying to find a needle in a haystack, especially when it comes to autoimmune diseases,” he says. “With most current methods, you destroy the tissue, which means not only that you get different immune cells mixed up but also that some cells die in the process. With this method, we preserve the cells where they are and see cells that would otherwise have been lost,” Jeff says.

Dr Mold believes that the ability to identify B cells is arguably the main benefit of this new method. “T cells have been a popular research target, while the B cells have been a little overlooked, especially in cancer,” he says. “But now we can track how B cells develop and expand directly in tissue.”

The study was financed by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society and the EU research and innovation programme Horizon 2020.

Karolinska Institutet Press Release

Contact:

Camilla Engblom

SciLifeLab Fellow

Assistant professor at Karolinska Institutet

Email: camilla.engblom@ki.se

Jeff Mold

Researcher at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at Karolinska Institutet

Email: jeff.mold@ki.se