Researching microbial interactions against all odds – meet Sarahi Garcia

Despite growing up in one of the least advantageous places for pursuing a research career, Sarahi Garcia has gone from a path of religious mission, with no scientific aspirations, to becoming a SciLifeLab Fellow with the goal of solving environmental problems.

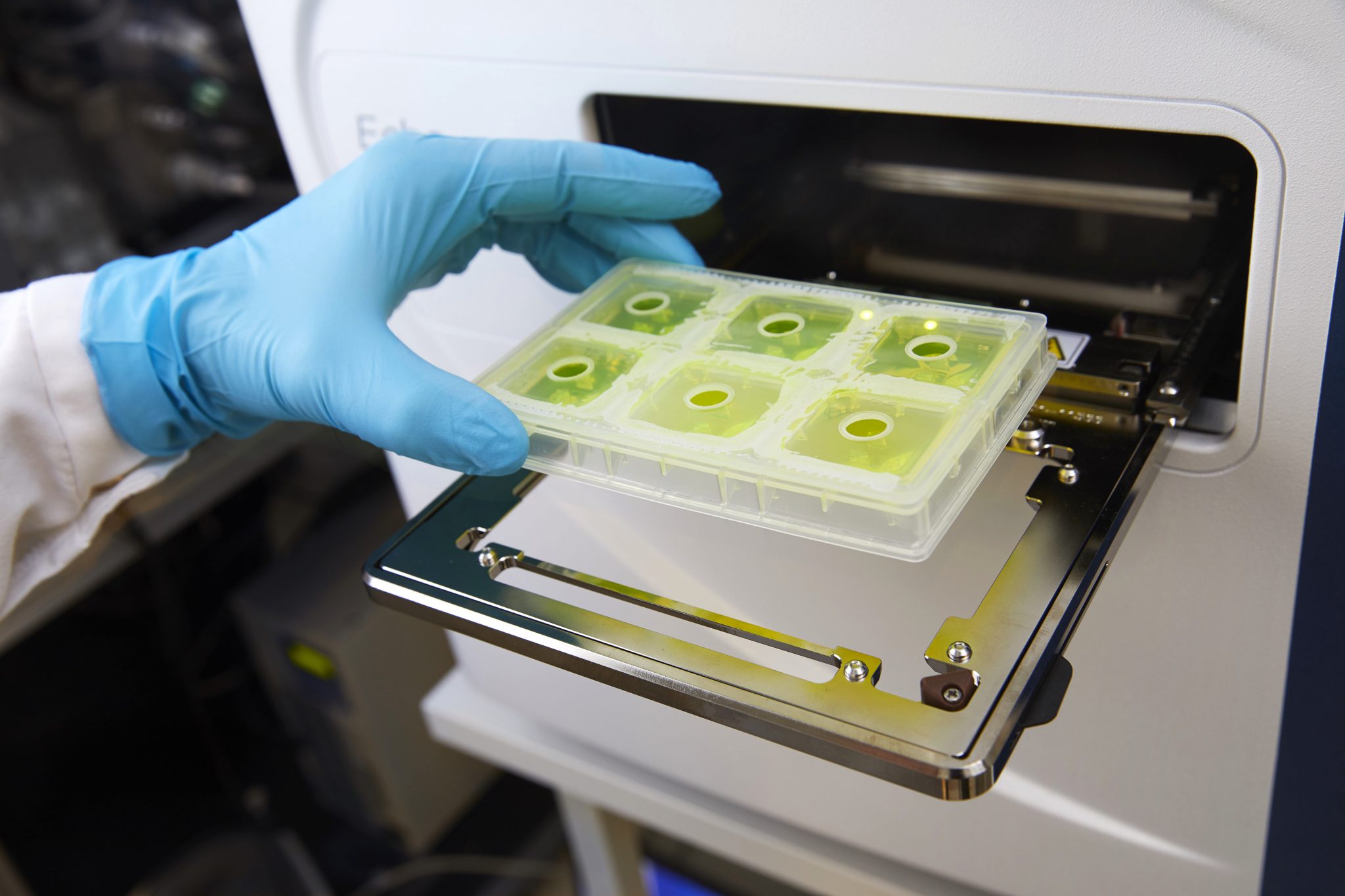

A lot of bacteria cannot biosynthesize everything they need, or detoxify their environment from their own waste products, so they depend on other bacterial cells around them. In one milliliter of lakewater there are on average one million bacterial cells. Taking the size of these cells into account, they are around 100 body lengths apart from each other. Despite this, they manage to influence each other. They can either detoxify the environment from waste products of other bacteria or produce biosynthetic molecules that other bacteria need. This is to a very large extent still a mystery, and it is precisely this Sarahi Garcia investigates. She wants to understand who needs who, how many needs different bacteria have, how they function together and what type of function they do together in the environment.

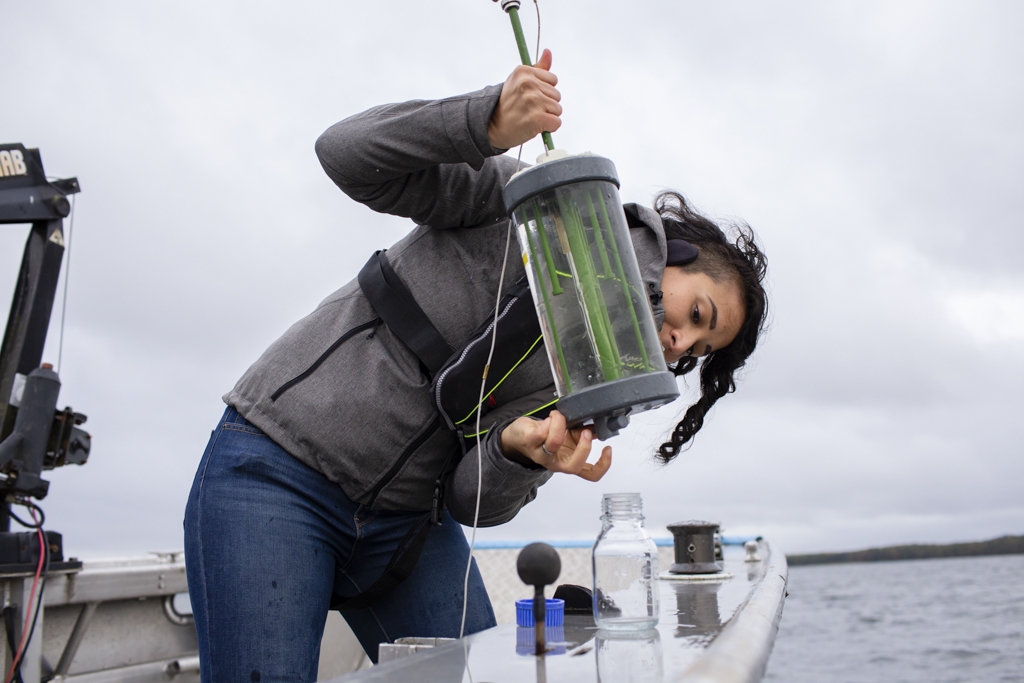

From her PhD and onwards, Sarahi has been working with water – as opposed to organic waste during her master’s degree. She hopes and believes that her research will be applicable in all kinds of fields, however. She hopes that growing, understanding and designing microbial communities can help us deal with problems facing society today, such as biological waste management, sustainable energy production and reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“This is my hope, that when we understand microbial interactions we can design and put together the right microbes to help us deal with our environmental problems”, says Sarahi Garcia.

Helping people through salvation

At the age of 18, Sarahi Garcia had lived in six different places – all in northern Mexico. She started her academic career with an undergraduate degree in biochemical engineering, in a public university in the state of Coahuila. This choice was made more because of chance than of an eager interest in either bio, chemical or engineering. She wanted to finish as quickly as possible and chose a degree where she would have the easiest time – since she was an ace at math, chemistry and biology, she picked the one education where she could squeeze in all her best subjects.

“I thought it was perfect, I’ll just go there, get it done with and then be a missionary”, says Sarahi Garcia.

Yes, a Christian missionary. Perhaps not the most common dream of a researcher. In fact, she had no aspirations of becoming a scientist at all. She had no reason to. Growing up with an illiterate grandmother, parents with no higher education and surrounded by people focused on gossip or faith, she had no examples of what a research career could mean – or that it even was a possibility.

“I was very good at paying attention in class, taking tests and studying the bible, but I knew nothing of the rest of the world”, says Sarahi Garcia.

Despite not having any higher education herself, Sarahi’s mother was determined that education was the way to a better life. Sarahi could become a missionary when a degree was completed.

It was during her university studies that Sarahi started to question her faith. She studied the bible intensely and it just didn’t make sense to her. During this time of questioning, two professors at her university were organizing a tour of two research centers in Mexico. She wanted to go, but despite having a part-time job as a gymnastics coach, she couldn’t afford to. To gather the money, she carried a cooler around in the 40 degree Celsius heat and sold homemade ice cream – chocolate, coconut and pecan nuts being the best sellers.

At the tour, a researcher at the Baja California Sur based center CIBNOR, was talking about his work on microbial diversity in the pacific, algae cultures and a more free view of knowledge than the memorize-and-repeat kind of learning Sarahi had experienced – she was hooked.

In parallel to her newfound passion, her faith in the bible had really started to collapse. She stopped going to church and broke up with her aspiring pastor for a fiancé. A highly religious community that did not understand her new way of life, together with a professor advising Sarahi to study a master’s degree abroad, made her next step a whole lot easier: she was applying for a study grant in the US.

She started practicing English through movies, a microbiology book in English she bought and by speaking to her professor. She passed the required English test and was offered a grant from the University of Georgia – all fees paid for and an extra 1,300 dollars per month.

A desperate need

Landing in Georgia was an overwhelming experience. Sarahi describes the area in Mexico where she has lived her entire life like a desert – gray and brown soil with concrete buildings. Flying over this new city, she saw lush green forests with moss hanging from the trees. She was amazed.

“You grow up thinking that the US take so much from us. They take land, they take all of our smart people, and then I landed in the US and saw all this richness in nature and it was beautiful. I had never seen anything like that in my life. Then I started wondering: “they already have so much, why do they want to take more from us?’”, says Sarahi Garcia.

As it turns out, while 1,300 dollars may be a lot of money in the north of Mexico, it will not get you very far in Athens, Georgia. After insurance fees and accommodation costs, there was not a whole lot of living to pay for with the grant. Money problems was not the only issue. The bubbly, outgoing, Sarahi who seems to be a natural when it comes to talking to unknown people, had a tough time in her new country of residence. She simply could not speak the language well enough. She spent so much time studying to be able to pass the tests and understand the professors that she could not bear to socialize in English, she needed a break. Instead, she called friends and family in Mexico.

One of those calls was the worst she has ever made. It was to her brother, who said that he wished that she had not broken her engagement with a Christian man, and that he wished that she would break up with her atheist boyfriend. The words were not very harsh, but they showed Sarahi that her brother did not understand her at all.

Sarahi eventually adjusted to life in the US, where she took on an interdisciplinary project on how to produce biogas from vegetable waste.

“Then I made different circles of friends. I had the engineering group, the microbiology group and in a way it felt a bit like me again, I felt a sense of community that I used to have in Mexico”, says Sarahi Garcia.

In the US, Sarahi met her husband – a German who studied in Georgia for a semester. After a visit in Germany she felt that she needed to learn yet another language if she was truly going to get to know him and his family. Back in Georgia, Sarahi started to learn German through a computer program, and then took an intermediate-advanced class at the university.

Now when she knew quite a bit of German, had a German boyfriend and there seemed to be more of an interest in recycling and bioremediation in Germany, going there for a PhD was not a terribly bad idea. What intrigued Sarahi the most during her master’s program, what she could not understand, was how the microorganisms in a community work together. For her master’s project she wanted to understand the biogas production process, for her PhD she now wanted to dig deep into microbial interactions. The Jena School for Microbiological Communication had an opening and it seemed like the obvious choice.

She did not just want the position, she desperately needed it. Coming from a family with low resources, she could not afford to take time off from school or from working. She has coached gymnastics, sold homemade ice cream, raised bunnies, embroidered shirts and worked in a bookstore.

“I just did anything that needed to be done to support myself, because there was no other way. So when I finished my masters and I still didn’t have a job lined up for me, I was scared. Truly depressed. I don’t think an average 23 year old European thinks like this, they don’t have to think like this”, says Sarahi Garcia.

She got the position she wanted and got her reallocation paid for by the university, something she could not have afforded on her own. She stresses that PIs have to think about this when they hire, good candidates from low and middle income countries simply cannot move across the globe without help.

A different background

When her new position as a SciLifeLab Fellow was confirmed, Sarahi Garcia wrote a twitter thread explaining how she almost lost hope of getting a tenure track position, but said that she was going to follow her dream until reaching it or having it “explode in her face”. So why did she have to almost get her face exploded to get a job? One reason is having an unprivileged background.

Sarahi was turned down 18 positions and from the feedback she got, it was clear that her CV was good – but not good enough. When people evaluate CVs, Sarahi felt, they do not see potential, they simply look at the raw numbers: how many publications, how many conference talks and so on. But to publish early, you need to be in an undergrad environment where it is possible to sign up for research. Sarahi Garcia did not have that luxury. On top of this, constantly moving between continents forces you to spend time learning new languages, rather than on your education. Having no money forces you to work, which, again, steals time from your studies. Knowing what steps to take when you are not born into a context where university studies are a given is another issue.

“Not everybody in academia comes from an academic family and already know during their undergrad that they’re going into academia and therefore do all the right steps, click all the right buttons and contact all the right people. Not everybody has this path, and if we truly want diversity in science we need to have more role models for people that come from different backgrounds”, says Sarahi Garcia.

Not everybody has the typical academic background, and Sarahi Garcia certainly does not. At age eleven, she had suffered two attempted kidnappings, one of which her uncle caught up with her assailant when he had already taken her a block away. Her mother’s house has been emptied down to the last carton of milk by robbers twice. Her brother has been held at gunpoint together with his wife inside their house for hours in another robbery. To get into the last house her mother owned, you needed to get past a spiked fence, barred windows and five locks on two separate doors. In Ciudad Juárez, where Sarahi lived during secondary school, close to 500 known so called femicides took place – killings of women, often with elements of sexual violence and torture, as well as the dumping of bodies in the desert or ditches – from 1993 to 2007. No, Sarahi Garcia does not have the average background of a researcher.

In her tweet, she quoted the Oscar speech of Lupita Nyong’o, who said that “no matter where you’re from, your dreams are valid”. This, Sarahi explains, is why she wrote her tweet: to instill hope for those who doubt themselves, as she and fellow minorities have done many times along the road.

It’s quite brave to share your failures as you did in that tweet, many would paint a picture of being a constant success.

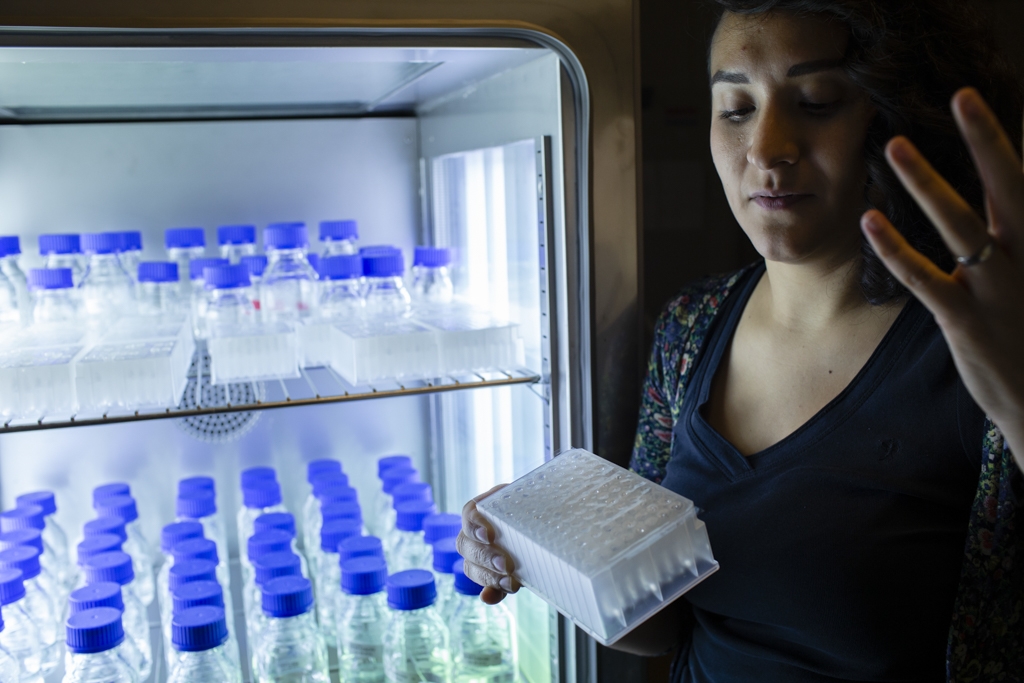

“What those people are also painting is the iceberg image. Success is just the tip of the iceberg, underneath are so many rejections, so many positions you didn’t get, so many experiments that failed. I mean, you just took a bunch of pictures of my failed test cemetery, we can learn a lot from being unsuccessful and then make the right decisions and go into a more successful direction”, says Sarahi Garcia.

So why was it worth continuing to pursue a career in science despite these hardships? Sarahi says it is the only way for her to not go insane. The curiosity driven brain of hers cannot get into too much of a routine, it needs to be fed puzzles and questions to not spiral down into depression.

“When I’m discussing science, when I’m discussing new questions, when I’m discussing new things we don’t know about, I just feel energized”, says Sarahi Garcia.

An unpredictable world

Two positions in Sarahi Garcia’s group are now open, a postdoc and a PhD position. This is the biggest challenge she identifies with creating a new research group: hiring people. From a few talks and perhaps a dinner, you are supposed to know if the person is going to be a good fit research wise, what the group dynamic will be and how efficient they are. On top of that, people get sick, go on parental leave and move away.

“If somebody would have asked me ten years ago what I wanted to do in ten years, I wouldn’t have a clue! There’s a lot of things that are unpredictable”, says Sarahi Garcia.

Sarahi is looking forward to pursuing her research questions, but also to mentor her new group members. She hopes she can be the role model she has been looking for.

“If I can be a good influence and help people in finding their path in who they are and who they want to become, that makes me feel happy. So in a way, it’s what I wanted to achieve when I wanted to be a missionary”, says Sarahi Garcia and laughs.

Text & photo: Niklas Norberg Wirtén