Gene mutation associated with epilepsy

Led by SciLifeLab researcher Niklas Dahl (UU), scientists from Sweden, Japan, France and Pakistan have discovered how mutations in the neurochondrin gene can contribute to epilepsy, delayed language development and developmental disorders. Signal transmission between nerve cells in the brain is greatly impaired because of the mutation.

The researchers began by examining an international database containing information about genetic analyzes of the entire human genome. The database consists of reports on abnormalities in the genome encountered in patients, collected by researchers and doctors from all over the world. The SciLifeLab SNP&SEQ platform, Genome Center, BioVis, UPPMAX and SNIC were all involved in the research.

Before analyzing the database, they had already identified three child patient cases involving the neurochondrin gene mutation in Uppsala. Through the database, they found an additional three children from different continents who had suffered from mutations in the same gene. Half of the patients had inherited the mutation (it requires traits from both parents) and for half, it had arisen in individual gametes.

“This mutation is another explanation as to why people suffer these conditions and could make it easier to diagnose affected individuals. These are common ailments often discovered in preschool children that are both causes for concern and raise questions for their parents. Did something wrong happen during pregnancy, childbirth or early childhood? Was there something wrong with our germ cells, and is it hereditary?”, says Niklas Dahl in an interview with Uppsala University.

“The mutations that we have found sometimes occur in single germ cells before the actual fertilization. It is then a coincidence that they happen to meet the neurochondrin gene and give these effects”, says Niklas Dahl.

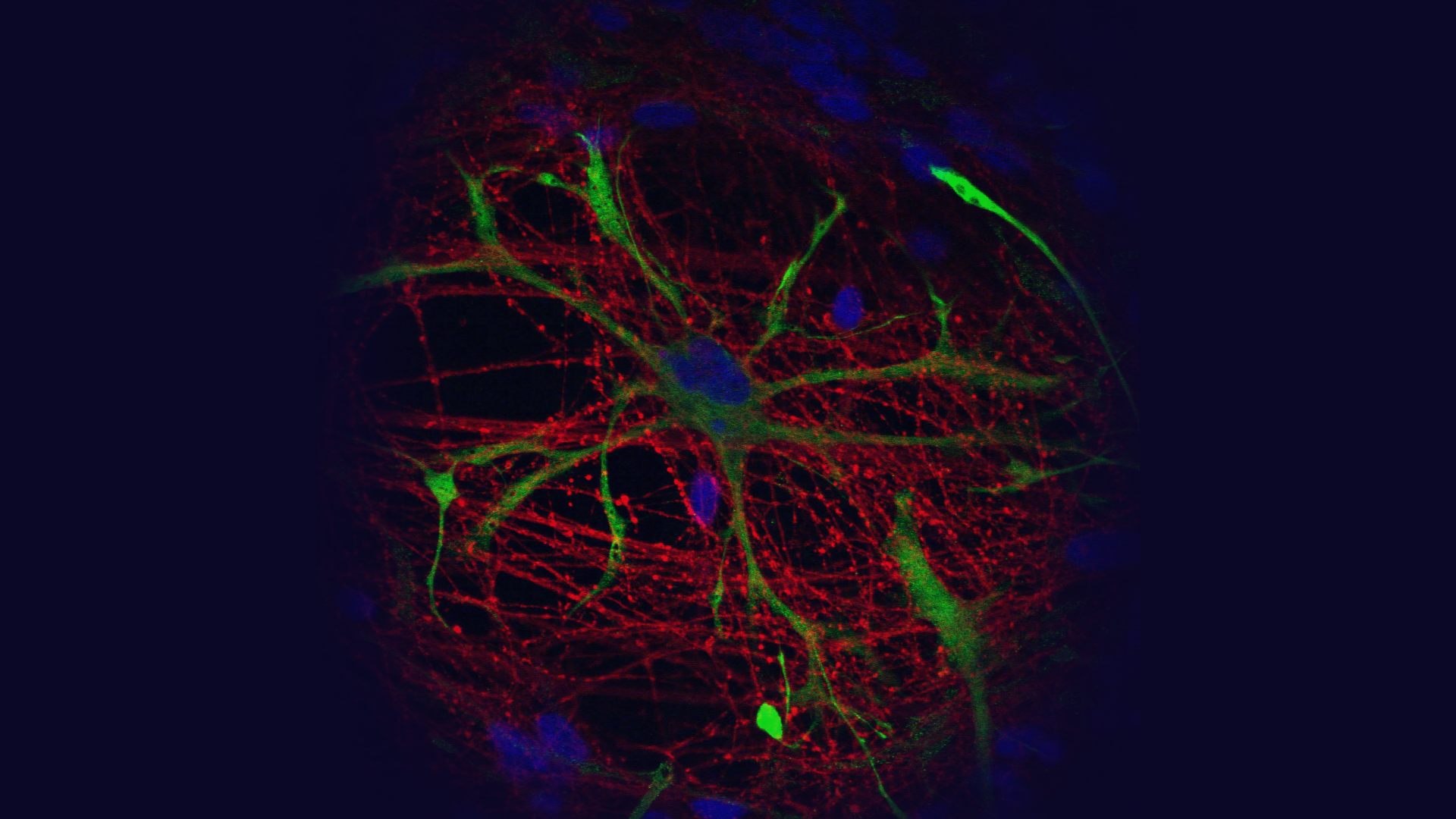

According to the researchers, nerve cells with neurochondrin mutations have fewer and shorter protrusions compared to nerve cells without mutations. With the mutation present not enough protrusions are developed to be able to reach nearby nerve cells which reduces their capacity to communicate. Another function of neurochondrin is to help transmit signals from the transmitter substance called glutamate between nerve cells.

The mutations result in an insufficient development of the “protrusions” making the nerve cells incapable of reaching reach other nerve cells that they must work with. Simply put, the contact pathways between the nerve cells decrease so that they cannot talk to each other. Neurochondrin also helps to transmit signals from the transmitter substance glutamate between nerve cells, and in children with the mutations, glutamate signaling deteriorates.

The mutations, therefore, cause several problems during brain development that leads to delayed language development, mild to severe developmental disorders, and epilepsy.

” We have added a piece of the puzzle to the understanding of the brain’s early development and for its normal functions. Most patients with neurochondrin mutations can be detected before the age of two. If we can, already before that, help the transmission of glutamate signaling, we may be able to alleviate the development of, for example, epilepsy in selected cases. From what we now know, we can also try to stimulate the formation of certain nerve projections in the nerve cells”, says Niklas Dahl.

Read the press release from Uppsala University in Swedish here.