The world’s oldest RNA extracted from woolly mammoth: “gives us a completely different picture”

The timespan of when RNA is possible to extract is now pushed back by tens of thousands of years, with researchers now hoping to spark a RNA revolution, after sequencing a woolly mammoth preserved in the Siberian permafrost for nearly 40,000 years.

There have been examples of scientists throughout the years showing that it is in fact possible to study ancient RNA. The RNA of more than a thousand years old seeds from Egypt were studied in the late 20th century, for one. Despite this, the general biologist has for a long time thought that RNA molecules are so unstable that they are not possible to study after a few minutes outside of a living organism — that they are almost immediately destroyed.

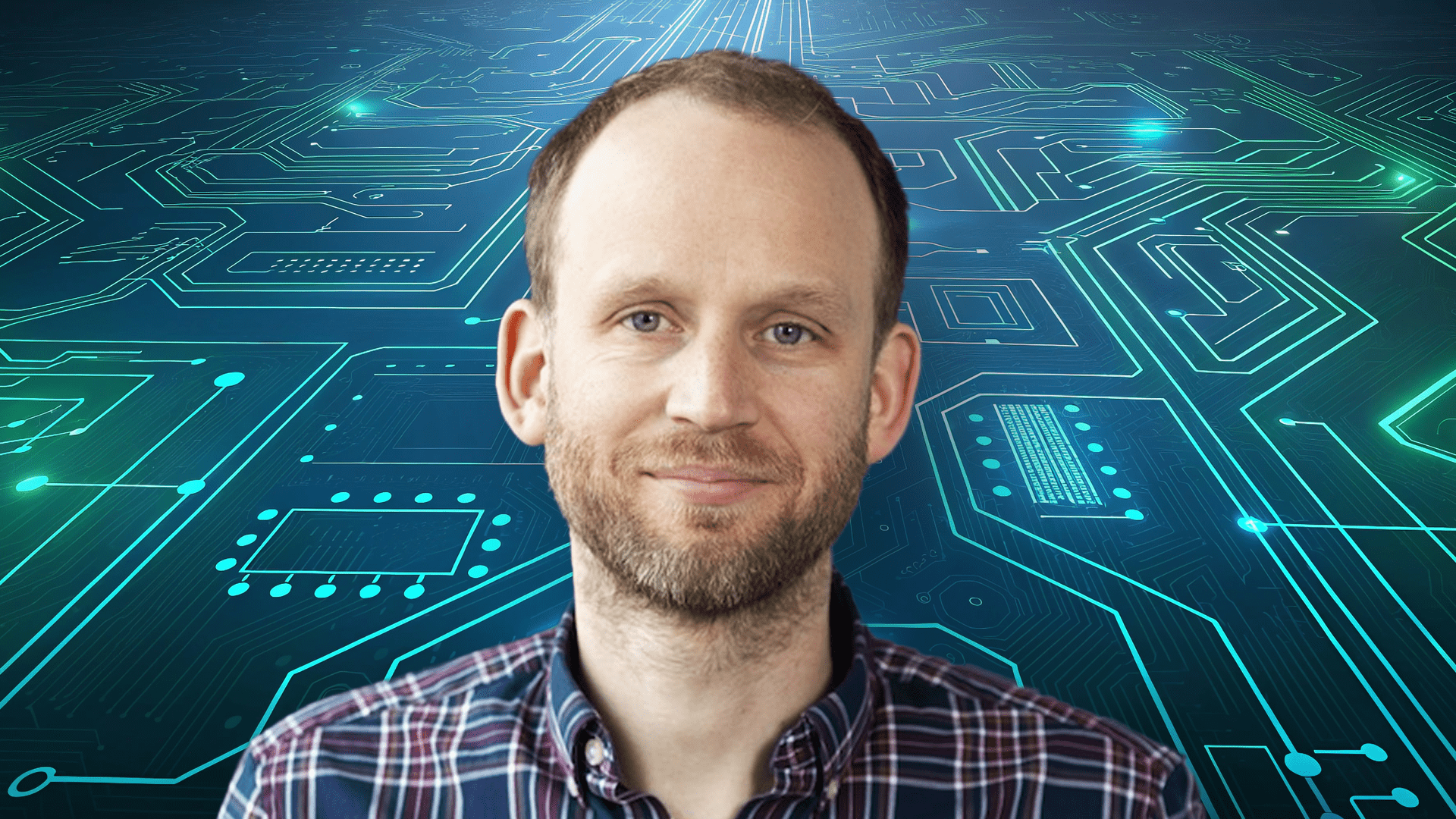

In the light of this, it is quite remarkable that RNA from a mammoth dating back 40,000 years now has been analyzed. For this article, we met with the “RNA guy” of the study, Marc Friedländer of SciLifeLab and Stockholm University, who teamed up with ancient DNA rockstar Love Dalén and lead author Emilio Mármol-Sánchez.

“What is quite important about this study is that it really pushes back the time span of when we can look at these RNA molecules, by tens of thousands of years. And looking at the RNA molecules is very interesting because it gives us all of this information that DNA can’t. We can actually learn something about gene regulation. You can tell something about health and stress of the organism,” says Marc Friedländer.

Ten times a millionth of a millionth of a gram

In defence of the general biologist, the examples have not been many and this landmark study was made possible in part by just trying, but perhaps mainly by technical development in recent years and lots of know-how.

What sparked Marc Friedländer to take on the project was a study from 2019, that sequenced RNA from a dog or wolf that died 14,000 years ago. At the time, the Friedländer group was working with RNA in single cells. Tiny cells that are about ten micrometers across and contain around ten picograms of RNA. So about ten times a millionth of a millionth of a gram.

“And then we thought, okay, hold my beer, we can also do this because we have the technical skills. We had a meeting with Love Dalén, who was also very excited about this,” says Marc Friedländer.

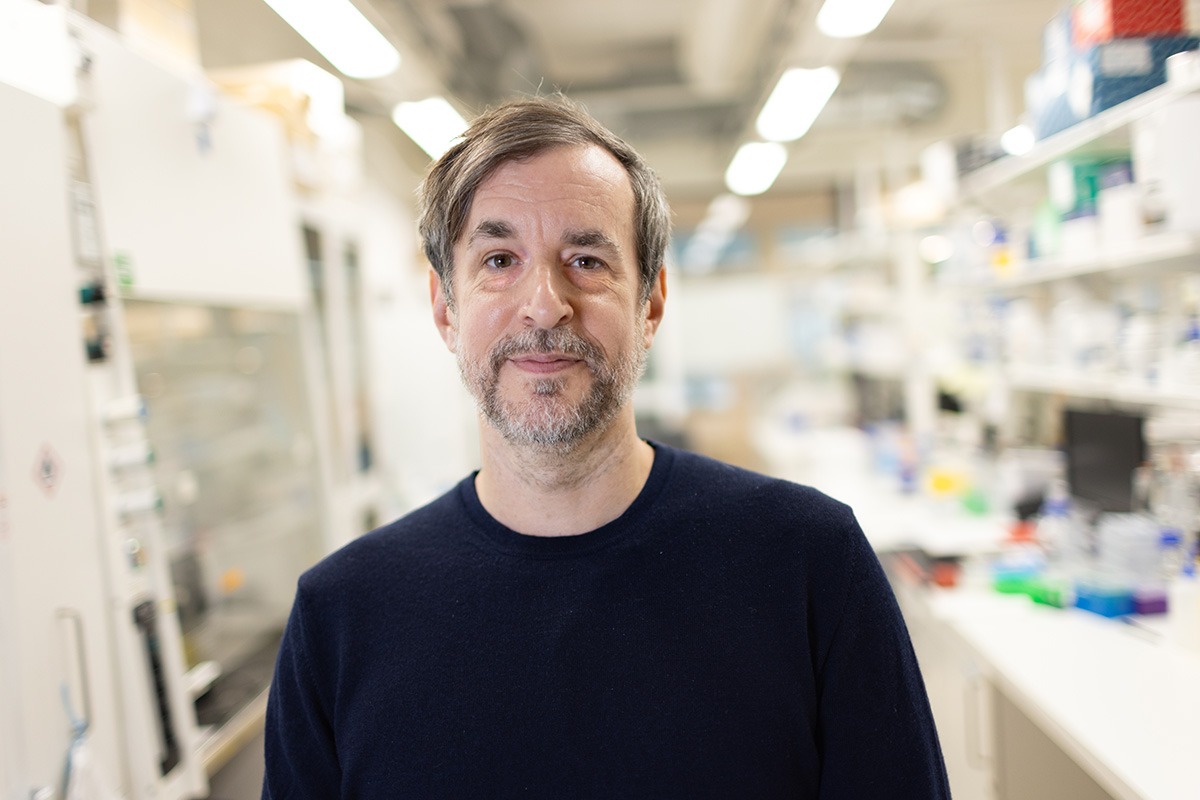

Apart from being excited, Love Dalén also had expertise in and access to a small part of a famous mammoth called Yuka, a young, well preserved, mammoth that died almost 40,000 years ago. Now came the challenge of getting some RNA out of this far from fresh tissue.

Broken into pieces

Emilio Mármol-Sánchez tried different techniques and finally got some RNA molecules, but then came another, bigger challenge: to through computational work sift out what is RNA from the mammoth, and what is RNA from sources like bacteria or microbes — or from the researchers themselves. Because of the age of this specimen, the RNA is broken into pieces, making this task very challenging.

To at least keep the researchers’ own RNA away, the tests were performed in an ancient DNA lab that has very strict protocols to keep things clean – and the researchers wear clothes looking like typical doomsday movie hazmat suits. Friedländer and colleagues also continuously made sure they were in fact analyzing mammoths.

“We found rare mutations in certain microRNAs that provided a smoking-gun demonstration of their mammoth origin,” notes Bastian Fromm, researcher at the Arctic University Museum of Norway (UiT), in the Stockholm University news article.

Attacked by cave lions

So what is the point of analyzing RNA that’s 40,000 years old, when you can look at DNA that is much older? Because with RNA you can tell not only what genes the animal had, but which of those genes were transcribed — that were active, simply put.

“It gives a completely different picture of what genes were actually turned on just around the time when the animal died,” says Marc Friedländer.

In this case, they found RNAs that indicate that the muscle they analyzed was slow acting, muscles that keep the mammoth stable, as opposed to muscles that are involved with running. They could also see that there were genes involved in stress being activated. Previous paleo-forensic studies, investigating the physical appearance of the mammoth, suggested that the mammoth had been attacked and wounded by cave lions, something the new study provides further evidence for.

“So probably it’s been running away from these predators and we could actually see this stress of the mammoth in the RNA molecules, which is pretty astonishing,” says Marc Friedländer.

The wrong sex

Another finding was two new microRNAs likely specific to mammoths and not present in modern day elephants, that may contribute to what makes mammoths unique, but they also found something quite surprising: the thought to be female mammoth, referred to as one throughout previous literature, was in fact male.

Researchers had through morphological studies, basically thoroughly looking at it, concluded that it was female. Some of the newly analyzed RNA, however, originated from a Y chromosome, which raised some eyebrows in the Friedländer group. They made further tests and confirmed through DNA that it was, in fact, a XY male.

“It’s still a bit of a puzzle, what has actually happened. But of course, after 40,000 years, the mammoth isn’t really in mint condition anymore. It is difficult to just from the morphology be confident about if it was a male or female,” says Marc Friedländer.

Uncovering disease like Covid-19

When you analyze RNA molecules, you can also detect RNA viruses. One well known example of this is SARS-CoV-2, which typically never exists in a DNA form.

“So if you only look at the DNA molecules, you’re blind to the history of the RNA viruses. And of course, it’s very interesting to potentially look at RNA viruses throughout the ages to try to reconstruct their evolution, to try to find out how have they evolved and co-evolved with their hosts, and maybe learn about specific things happening around the time when RNA viruses become able to cross species barriers and maybe jump from one animal to the next,” says Marc Friedländer.

Aiming to get a hundred times better

“One of my dreams right now is a bit more on the technical side, which I think will enable future studies. We get a lot of RNA molecules from these different samples, but we are probably missing most of them,” says Marc Friedländer.

He knows from careful benchmarking that the methods they use are optimized for small RNA fragments. Even under optimal conditions on fresh tissues, they detect around one RNA molecule in a hundred.

“If we could make these methods more sensitive, then we could probably increase the yields that we get from all of these samples, very substantially. And a lot of these molecules that we find, are probably very damaged in different ways. If we could develop methods that are good for damaged RNA molecules, then we might get 100 fold more molecules. That could really bring about a revolution in RNA profiling in all kinds of samples,” says Marc Friedländer.

An abundance of old animals

Another challenge going further is the lack of 40,000-year-old animals frozen in pristine condition. There are however an abundance of animals preserved in other ways, easily accessible. Where? In museums all over the world. These specimens are typically not frozen, but a few years back Marc Friedländer and collaborators managed to sequence RNA from a Tasmanian tiger that had been hanging out at a museum in room temperature for 130 years. This animal had not been frozen, but had rather been preserved by desiccation — by becoming very dry.

“So while there might not be so many specimens around that are as old and as uniquely well-preserved as the Yuka mammoth, if you go to museums and collections all over the world, then you will find tens of millions of animal specimens that are very dry and might contain a lot of RNA and a lot of interesting information, about for example the history of viruses,” says Marc Friedländer.

Speaking to Marc, it is clear that the exploration of RNA is just the beginning.

“I think these days people are just realizing that, yes, under most conditions RNA is a very unstable molecule, but under specific conditions RNA can actually persist for hundreds or even thousands of years”.

Hear more from Marc Friedländer, Love Dalén (Stockholm University) and Emilio Mármol-Sánchez (University of Copenhagen) in the Stockholm University news article.

Text and portraits of Marc Friedländer: Niklas Norberg Wirtén.

The article “Ancient RNA expression profiles from the extinct woolly mammoth” is published in the journal Cell.